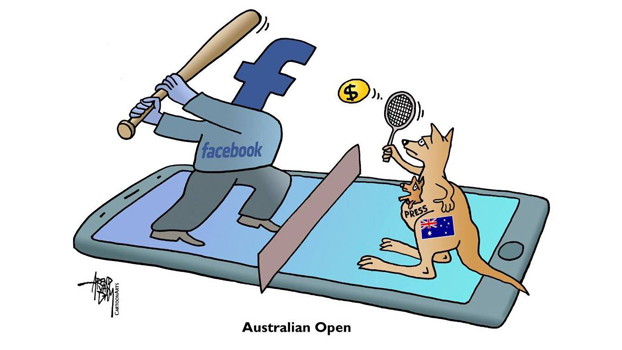

Australia’s face-off with Facebook is of global import

After a face-off between the Australian government and Facebook, in an outcome that has global import, Big Tech will begin paying for using news content from traditional Australian media.

After speaking to Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg six times in 36 hours and what the BBC called “robust negotiations,” on Feb. 23 Australian Treasurer Josh Frydenberg hailed the resolution to the internationally high-profile dispute with the precedent-setting outcome. “Australia’s move to put in place a world-leading mandatory code has seen us become a proxy in the battle that involves the rest of the world,” he said with a sense of triumph.

In 2017, Australia’s competition regulator recommended a voluntary code with the aim to redress the negotiating imbalance between the world’s major digital platforms and local media businesses. Acting on its recommendations, in 2019 the government asked media companies to come to an agreement on a voluntary code.

Last April the regulator said a voluntary agreement was unlikely and it was tasked with drafting a mandatory code. The draft law was released in July and the government subsequently introduced a bill in Parliament to address the concerns. Google and Facebook rejected the requirement to enter into payment negotiations with media companies, with mandatory arbitration by an independent adjudicator if no agreement was reached. Google subsequently relented on the threat to pull out its search engine and began negotiating agreements with local content generators, but Facebook held firm.

Australia’s draft code was different from the European approach in one crucial respect. The latter linked payments to copyright but without including an enforcement mechanism in the agreement. For Australia, it is more of a competition issue with the potential for abuse of market dominance by global Big Tech.

The latter’s main objection was to the coercive features of Australia’s code. Several of Europe’s major publishing groups called for the Digital Single Market Copyright Directive, due to come into force in June, to be expanded to include a law similar to Australia’s media bargaining code. The principle behind Australia’s fight with Big Tech thus has wider international resonance.

The publishers’ argument is simple. By including their content in their search engines, tech giants are guilty of theft. Frydenberg informed Parliament on Feb. 18. that of Australia’s approximately $9 billion annual online advertising, about $4 billion goes to Google and $2 billion to Facebook. No other sector operates with a business model that effectively steals the work of other professionals to generate advertising revenue, but refuses to pay those who created the content. Defenders of Facebook argue that it had merely called the publishers’ bluff: It cannot be compelled to link to media stories. If the publishers believe sharing links is tantamount to stealing, fine, Facebook would stop doing so. In effect the corporate bosses of news organizations want to have their cake, eat it and make Big Tech give them money for doing so. Others suspect the government has acted mainly to protect the interests of Rupert Murdoch’s media group in Australia.

The draft law attracted global interest because of its precedent-setting relevance to a shrinking traditional media just about everywhere as advertising dollars are being hoovered up by the internet giants piggybacking for free on the costly news reporting business of traditional media. While Google blinked on its threat to exit Australia and agreed to sign a deal with local publishers, Facebook escalated the dispute on Feb. 18 by blocking all Australian-sourced news from its site.

In a spectacular act of reputational self-harm in the middle of a global pandemic, the ban affected an extensive range of public services like weather forecasts, fire and rescue, emergency and crisis, state health departments and even charities. Australian users were blocked from accessing local and international news.

Australian publishers were blocked from posting and sharing links to their pages. In one clumsy strike, Facebook unified the entire Australian political spectrum, alienated its users for the contempt displayed toward them and underlined just why tech giants require enforceable regulation as a check on their extraordinary market power. Australian news content returned to Facebook on Feb. 26.

The massacre of Muslims at prayer in mosques in Christchurch in March 2019 was committed by an Australian resident of New Zealand. Australians haven’t forgotten that he live-streamed it on Facebook to a global audience.

The annual Edelman Trust Barometer 2021 survey showed a fall in trust in social media to barely one-third of people. Facebook’s ham-handed retaliation also confirmed that it is indeed a publisher that believes its near-monopoly market dominance has made it invincible against mere governments. In a quick poll of Australians after Facebook’s ban on Australian news and users, 56% said the ban was unjustified and 36% threatened to drop Facebook if the ban wasn’t lifted. Only 19% trust Facebook and nearly half believe that social media companies should pay publishers for posting their news content.

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison described Facebook’s decision to “unfriend” Australia as “arrogant” and “disappointing” and said he would not be “intimidated” by the tech giant. Australian businesses and the government began redirecting advertising money away from Facebook in significant volume. On Feb. 18, Morrison raised the topic of the media platform bill in his phone call with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi as part of a global diplomatic offensive to mobilize support for Australia’s proposed law. The Times of India described the effort to curb the power of Big Tech “a watershed moment.”

Politicians, news publishers and rights groups in several countries joined in the chorus of criticisms directed at Facebook. Julian Knight, who chairs the U.K.’s parliamentary oversight committee on the media, called it “bullying.” The Washington Post wrote on Feb. 19 that Facebook’s “brute force tactics” underscore “how much power it has to sidestep regulations it doesn’t like. And that’s emboldening [U.S.] lawmakers who already believe there’s a case for Facebook to be broken up.”

The leverage of the coercive bargaining code delivered a mostly positive outcome for Australian publishers. Perhaps the robustness of the global backlash helped to concentrate Facebook executives’ mind. Facebook has since “re-friended” Australia. Frydenberg said on Feb 23. Google also backed the four technical amendments to the draft media code, including a one-month warning period before a digital platform will be forced to comply with the proposed legislation, giving parties more time to reach a private deal before the market regulator intervenes. With support from the Labor opposition, the legislation was passed in both houses on Feb. 25 and will ensure “news media businesses are fairly remunerated for the content they generate,” Frydenberg said.

Ramesh Thakur is an emeritus professor at the Crawford School of Public Policy, The Australian National University.

Source: Japan Times