Why are interest rates falling in Southeast Asia?

Thiam Hee Ng

It was not long ago that economists were fretting about interest rate rises in Southeast Asia. But in 2019, the mood has distinctly shifted among central banks in the region. Malaysia’s Bank Negara cut its interest rate in May by 25 basis points, the first cut since July 2016. The Philippines reduced its interest rate in May and August, reversing the cumulative 175 basis points increase in 2018 as inflation spiked. There were three rate cuts from Bank Indonesia after aggressively raising interest rates in 2018 as the rupiah weakened. Thailand — in a surprise move — cut its benchmark interest rate by 25 basis points in August, reversing a similar size increase towards the end of 2018.

While each of these countries has its own domestic reasons for rate changes, there are several overarching global trends prompting the shift towards looser monetary policy.

First is the general slowdown in global economic growth. As second-quarter GDP growth numbers started trickling in, it became clearer that growth momentum has slowed among the major economies. The inversion of the yield curve in the United States is raising fears of an impending recession. US–China trade tensions are also starting to take a toll — export growth suffered amid rising fears the situation could worsen as secondary effects feed through the supply chain.

Southeast Asian economies, which are generally open, have started seeing the impact of this slowdown with growth coming in lower than expected in the first half of 2019. Cutting interest rates can be a useful preemptive move to provide additional stimulus to stave off further deterioration in economic activity.

The generally benign inflation outlook across the region also allows for policymakers to cut interest rates. With weaker growth, there is little demand side pressure on prices. On the supply side, oil and food prices are relatively stable. Southeast Asian countries have also moved fast to address supply side bottlenecks that contributed to inflation in the past. With less to fear from inflation, central banks can be more aggressive in pushing for lower interest rates.

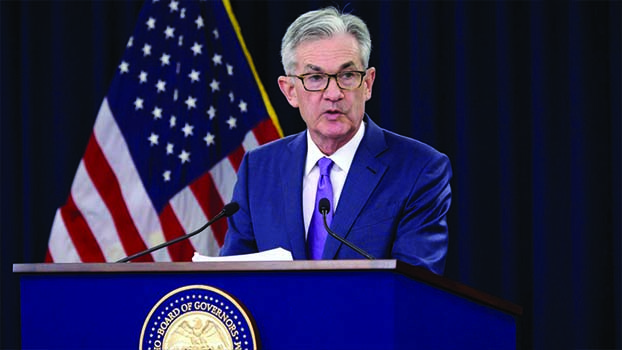

Central banks in the region have additional room for manoeuvre with both the Federal Reserve and European Central Bank cutting rates. The Federal Reserve reversed course and reduced its interest rate twice, in July and September 2019, each time by 25 basis points. This marks the first time the Federal Reserve has cut rates since the end of 2008. In early September, the European Central Bank also opted for more easing by lowering the interest rate on its deposit facility and restarting quantitative easing. The shift towards looser monetary policy reduced the downward pressure on Southeast Asian currencies which picked up when the Federal Reserve was hiking its rate.

While the interest rate cuts should help support economic growth, it may not alone be enough to offset the impact of a slowing global economy on the region’s growth. Interest rates are already relatively low and the cost of financing may not be the main factor deterring businesses from investing. For example, uncertainties about future trade policies and more downbeat business sentiments may be more significant. On the consumer side, high household debt levels may constrain individuals’ ability to take advantage of the lower rates.

Southeast Asia’s central banks also need to carefully balance the benefits of lower interest rates on the economy with the risks of higher vulnerabilities in the financial system. Too much cheap and easy liquidity could fuel asset price bubbles or lead to firms being overleveraged. It is important that policymakers be vigilant towards signs of excessive risk building up in the financial system. They should also be ready to deploy macroprudential measures where needed to alleviate any potential risk build-ups.

Monetary policy alone cannot do all the heavy lifting. Fiscal policy will need to do its part as well. In countries where there are infrastructure gaps, front-loading infrastructure spending can help bolster demand in the short-term and pay large dividends later down the road. Another area ripe for fast-tracking spending to cushion against the slowdown is in skills and training. This additional spending can help prepare the workforce for the challenges posed by the Fourth Industrial Revolution and set them up for careers in new fields. But it will also have to be balanced against the availability of fiscal space and existing debt levels to make sure government finances do not become overstretched.

This should be a wake-up call for countries to hasten efforts towards diversifying their economic base. As the recent trade conflict demonstrates, there is a risk in concentrating in a few products. The region’s economies could potentially benefit from the relocation of some manufacturing capacity in the region. This can help countries broaden their manufacturing base and move up the value chain by undertaking higher value-added activities. There has been an encouraging pickup in foreign direct investment flows into the region in 2019 as firms relocate production in response to the higher tariffs. Further reforms should be undertaken so that countries can continue attracting inflows even after trade tensions ease.

Thiam Hee Ng is Principal Economist in the Southeast Asia Department at the Asian Development Bank